By Hemant Tewari and Manjari Tripathi

Introduction

Weather significantly impacts a country’s economy, particularly in sectors like agriculture and raw material production. The connection between weather and economic prosperity has led to the exploration of weather modification. This intentional adjustment of atmospheric conditions aims to alter local weather patterns through techniques such as precipitation modification, hail suppression, and fog dispersion. Weather modification has far-reaching effects on sociological, ecological, and economic factors, with potentially unintended consequences. India’s drought-prone states, which are vital to its economy, face challenges in achieving ambitious growth targets. The increasing relevance of climate change calls for a regulatory framework for cloud seeding and weather modification to address the impacts of floods, landslides, and droughts on economies and millions of people.

Historical Background

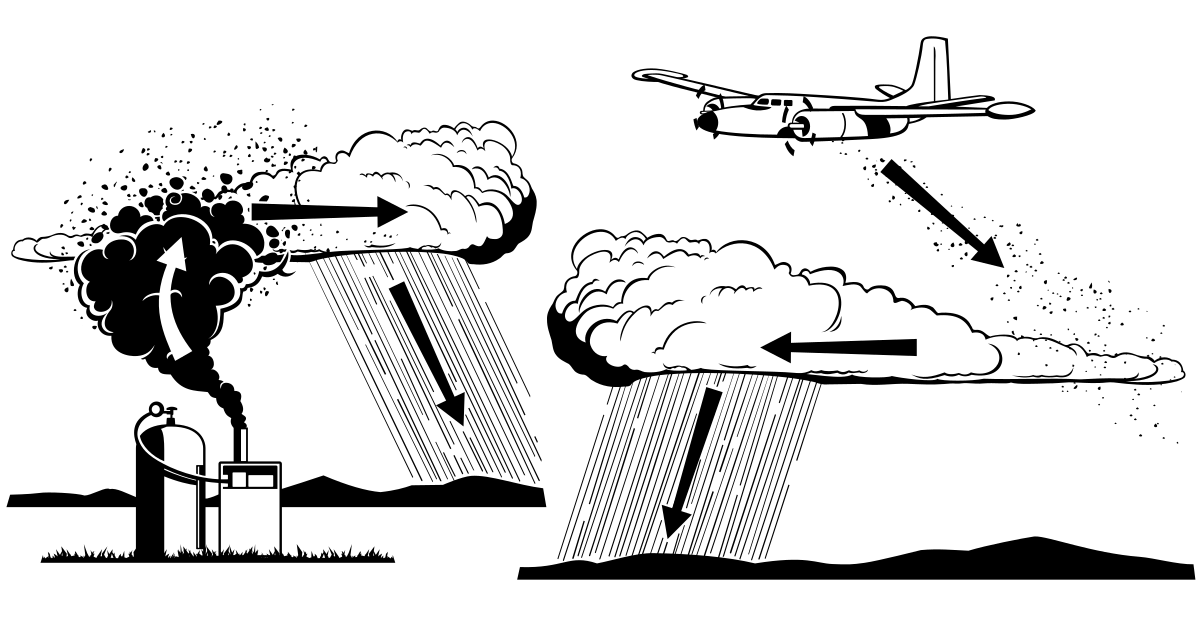

In the 1940s and 1950s, weather modification gained popularity as a promising field of study. Cloud seeding, first experimented by Vincent Schaefer in 1946 using dry ice, captured attention for its potential to manipulate the weather. The United States, motivated by the Cold War, pursued weather manipulation for military purposes in the late 1960s and early 1970s through programs like Project Stormfury. Australia’s Snowy Hydro and India’s Tata Company also initiated cloud seeding projects. India’s Committee on Atmospheric Research recommended a dedicated research unit in 1953, leading to the establishment of the Rain and Cloud Physics Research (RCPR) unit. RCPR conducted successful cloud seeding programs using salt generators, resulting in a 20% increase in rainfall. The Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM) absorbed RCPR and became a leading climate research institute for cloud seeding exploration. However, challenges and issues persist in weather modification techniques, requiring attention before deploying cloud seeding as a solution to climate change and global warming.

Challenges

Scientific Concerns

Weather modification involves complex and chaotic atmospheric systems, making it difficult to predict and control the outcomes of such interventions. For example, attempts to lift fog through mechanical mixing can sometimes worsen visibility instead of improving it. The unpredictability of weather modification outcomes has made it challenging to provide definitive proof of success. The lack of scientific understanding and the absence of rigorous experimental controls have also hindered the validation of weather modification techniques.

Legal Concerns

Weather modification raises legal questions regarding property rights and liability. Early court interpretations debated whether individuals had property rights over clouds and the rain they produced, but it was eventually established that rain belongs to everyone. Determining legal liability for weather-related damages can be complicated, as it is challenging to prove that a specific weather event causing harm was directly caused by weather modification efforts. Regulations and licensing exist at the local and state levels to ensure competence and protect the public from incompetent practitioners. Even if one state permits weather manipulation, a neighboring state might not. If a seeded cloud crosses the state boundary, things may become quite challenging.

Internationally, India is a signatory to the 1978 United Nations Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques (ENMOD Treaty). The treaty prohibits the military use of weather modification as a weapon, with limitations on the scale and severity of the effects.

Moral and Ethical Concerns

Weather modification raises moral and ethical concerns due to conflicting preferences for weather conditions among different groups, such as farmers and resort owners. Environmental consequences and unintended effects on ecosystems further add ethical complexities to the practice.

Regulations around the world

Internationally, the right of governments to utilize transboundary watercourses for cloud seeding is recognized under Article 5 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses. They must, however, comply with the requirement that they do not significantly impair the environment of neighboring states that share the same watercourse. Parties are required by Article 7 of the Convention on Biological Diversity and its Nagoya Protocol to make sure that their seeding procedure has no negative effects on biodiversity. Additionally, the clause mandates that parties secure approval from nearby communities before beginning planting. Additionally, the emission and transportation of air pollutants as a result of cloud seeding are governed under Article 2 of the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution.

The US Weather Modification Act creates a legal foundation for cloud seeding. This calls for acquiring permissions from the appropriate US state agencies and abiding by safety and environmental regulations. States in the USA have independent regulations namely the Colorado Weather Modification Operations Act, Texas Weather Modification Act, and North Dakota Atmospheric Modification Law. Similar guidelines are laid forth in the Chinese Regulation on Weather Modification, which also demands that any negative consequences brought on by cloud seeding be minimized.

Case laws

Slutsky v. City of New York

In the case of Slutsky v. City of New York, the plaintiff, Slutsky, sought an injunction to stop the city’s artificial rain experiments, which aimed to alleviate a severe drought. The trial court denied the injunction, stating that the plaintiffs lacked legal rights to the clouds and failed to demonstrate irreparable harm. The court recognized the conflicting interests between potential inconvenience to Slutsky’s resort and the need to provide water to millions of people. It concluded that protecting public welfare outweighed speculative private concerns, and therefore denied the injunction, as the plaintiffs lacked both factual and legal grounds for their request.

Summerville v. North Platte Valley Weather Control District

A property owner within a weather control area named Summerville contested the legality of a 1957 Nebraska state legislation. Summerville, who resided outside the district but was impacted by its choices, was not given the chance to be heard. The state legislation was found to be unconstitutional by the trial court and the Nebraska Supreme Court. Notably, neither weather manipulation nor landowners’ rights to cloud water were discussed in the Supreme Court’s ruling. Instead, it concentrated on the flaws in the law that were similar to those in a 1924 law that had already been declared unconstitutional. The court thus decided that the law was against constitutional norms.

Indian Regulations

Clear legal and regulatory frameworks are necessary to provide effective monitoring, environmental preservation, and public safety when it comes to weather manipulation. In India, there is presently no comprehensive legislation that covers weather modification explicitly, which might impede its development and application.

India needs legislation to tackle cloud seeding techniques. Addressing climate change will be the most crucial theme of the next century, proper legislation is imperative to regulate measures, such as cloud seeding, which will be vital for mitigating the effects of climate change. India currently lags behind nations like China and USA which have their regulations covering, inter alia, cloud seeding.

India will need to enter into Public-Private Partnerships(PPP) soon to fully address global warming and meet its 2070 COP26 emission targets. PPPs working in complex areas such as weather modification require a regulatory framework to work within.

Weather modification becomes even more complex in developing countries like India which do not have the infrastructure to support cloud seeding and diverse climatic conditions. The exigency for regulation of such Byzantine techniques in India is advancing.

Government regulation of cloud seeders in the USA often involves two steps. The government first issues licenses to specific cloud seeders. The government gives a licensed cloud seeder a permit to operate at a certain location and within a defined window of time. Before granting permission to a cloud seeder, several states need public hearings. A multi-pronged approach similar to the USA could also be emulated in India.

India can model a domestic bill along the lines of the Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques (ENMOD). The bill should create a regulating agency for weather modification, shed light on the role of interest groups, determine liability in cases of unintended consequences; whether absolute or strict liability is to be applied, install barriers to military use of such techniques, settle legal questions regarding property rights and liability in case of weather-related damage and formulate eligibility for granting license to private companies. In addition to addressing the legal concerns, the bill should make endeavors for research in weather modification which would remove ambiguities regarding the efficacy of cloud seeding.

Conclusion

India has a chance to shift away from its policy of reactionary legislation-making wherein laws are made after disasters or accidents. The government is caught lacking strict regulatory oversight and is left red-faced. Such public embarrassments can be avoided by staying ahead of the curve, a weather modification bill would certainly be the answer. India has no framework to cover weather modification-related disasters that would leave litigants to the mercy of generic laws which might not provide adequate relief. India can use regulations to instill proper procedural and substantive approaches before the weather modification industry becomes a crucial part of the economy.

Writers are third-year students

Dharmashastra National Law University, Jabalpur